This is a success story virtually without equal in women's sports in the post-Title IX era. A story not only about the success of one remarkable young woman, but about her parents and those, like me, who were privileged to watch her grow from a starry-eyed and talented teenager to the mature, self-assured woman she is today; a story which should serve, not only as an inspiration to any youth athlete who wants to reach the elite level in their sport, but for their parents as well.

Two days ago, Angela Ruggiero held a press conference to announce her retirement from women's ice hockey, two weeks after she told me of her decision.

As it is for any elite athlete, retiring was a bittersweet moment for Angela. Bitter because a shoulder injury would cut short her hope to compete for another gold medal in a fifth Olympics in 2014. Sweet because she could now devote her incredible energies and talents full time to representing the athletes of the world on the International and United States Olympic Committees, by beginning the next chapter in an odyssey that I have been lucky enough to watch, as the profiles of athletes on Olympic television broadcasts used to say, "up close and personal."

Any attempt to recount Angela's accomplishments, not only on the ice but off, since she won gold at a member of the Women's National Team at the 1998 Olympics in Nagano, Japan as a high school senior at age 18, won't do her career justice, so for those not already familiar with her stellar athletic -and personal - resumé I direct you to her website. But here's just a partial list:

- a collegiate career at Harvard highlighted by an NCAA championship, four straight first-team All-American selections, a Patty Kazmaier Award, first-team NCAA Academic All-American honors;

- a sixteen-year career on the Women's National Team during which she appeared in an all-time record 256 games and tallied 208 points on 67 goals and 141 assists, highlighted by four Olympic medals (one gold, two silver, one bronze), four World Championship golds and six silvers in 10 appearances, and selection as the top defenseman at the tournament four times; and

- a history-making appearance on January 28, 2005, when she and her brother, Bill, competed for the Central Hockey League's Tulsa Oilers, becoming the first-ever brother-sister tandem to play in a professional hockey game in North America; a contest which also saw Angela become the first female non-goalie to play in a professional hockey game in North America.

In announcing her resignation, she told USA Hockey that she felt "honored and privileged to have represented the U.S.A. program over the past 16 years." Listening to press conference, all I could think was how honored and privileged I am to have known Angela for the past eleven years of her journey.

Harvard

I first met Angela in the spring of 2001 as she began training for her second Olympic games in Salt Lake City, Utah. Then a junior at Harvard, Angela agreed to become MomsTeam's ice hockey expert, and began posting fascinating blog entries about her experiences as a member of the Women's National Team as it prepared for the Olympics, including contributing to an article I wrote about the traumatic day when the final cuts were made, leaving some of her teammates out in the cold looking in. Angela's dad, Bill, who had coached Angela and her brother, Billy, also chipped in with articles.

I was, I have to admit, a bit envious of Angela and the generation of female athletes of which she was a part. As an athletic young girl growing up in the pre-Title IX years, the only times I saw women athletes competing were at the Olympics. In the four years between Games, the spotlight seldom shone on women athletes, so my female role models were few and far between. As a girl who learned to ski at a very young age and spent all of my winter vacations in Vermont on the slopes of Bromley and Stratton with my father, one of my dreams growing up was to be a giant slalom skier in the Olympics. So, as a lifelong fan of the Olympics, especially the Winter Games, it was a thrill to get to know Angela, not only because she was an Olympic athlete, but because she helped make my lifelong dream of attending one in person a reality.

Birthday surprise

My trip to Salt Lake for the 2002 Olympics, officially the XIX Olympic Winter Games, could not have been more memorable, and Angela had a lot to do with making it so special. When she learned that I would be attending, she gave me one of only four passes each athlete was given to the AT&T Family Center, where I had a once-in-a-lifetime chance, along with her brother, sister and mom, Karen, to get to know many of the athletes and their families, eat all my meals and watch all of the events that I was not able to attend in person on huge wide-screen TVs.

The highlight of my stay came on the evening of February 15, 2002, 50 years to the day after another skating legend from Harvard, Dick Button, won a gold medal in men's figure skating at the Olympics in Oslo, Norway, and the day I was born.

Just before dinner in the ATT Center, Angela, along with the entire U.S.A. Women's Hockey Team, surprised me with a birthday cake. Along with Angela's mom Karen, sister Pam and my triplet sons, they then serenaded me with "Happy Birthday." Next to the birth of my triplets, it was one of the most memorable and special moments of my life.

Soon after the Olympics, Angela joined the Board of Directors for the Teams of Angels, a non-profit organization I had established to educate parents on ways to prevent catastrophic injury and death among youth athletes. Angela demonstrated through her work for Teams of Angels a genuine passion to help kids in sports, a passion she displays every time she meets a young hockey player, and in teaching girls to play hockey at her camp every summer.

Special invitations

In 2004, when Angela was a finalist - for the fourth straight year - for the Patty Kazmaier Memorial Award, bestowed annually on the top player in NCAA Division I women's ice hockey, she honored me with an invitation to attend the award's dinner in Providence as her guest. You can only imagine the joy I experienced when Angela was named the winner. When she graduated with honors from Harvard later that year, I wasn't able to attend, but have kept the engraved invitation as a cherished keepsake.

I wasn't able to watch Angela win her third straight medal at the 2006 Winter Games in Turino, Italy, but she continued to stay in touch, calling or e-mailing me on a regular basis to share news of her team's and her own individual successes, including visits to China, her appearance on "Celebrity Apprentice", the satisfaction of beating arch-rival Team Canada for gold at the World Championships in 2008 and again in 2009, and gearing up for a fourth Olympics in 2010.

Vancouver

With the Olympics in North America again, it was time for another trip to the Olympics to watch Angela, with a team of veterans, including her Harvard teammate, Julie Chu, and newcomers, battle once again with Team Canada for gold in Vancouver. Angela made sure that I had tickets to the gold-medal game which, no surprise, was yet another re-match with Canada's Haley Wikenheiser - like Angela, 31 and competing in her fourth straight Olympics.

Canada Hockey Place was a sea of red: red Canadian flags, red coats, red hats. I still wonder to this day about how the tickets were allocated. Every other time I had seen Angela play with tickets that she had gotten, I had a great seat. This time around, we were in nosebleed heaven, surrounded by screaming Canadians, which made things all the more difficult when a brilliant game by the Canadian goalie kept the Americans off the scoreboard in a 2-0 win for Team Canada, its third-straight gold, and, I am sure, the most satisfying, coming as it did on home ice with all of hockey-crazed Canada watching.

Ironically, not only did Angela add another Olympic silver to her trophy case, but the trip to Vancouver had a silver lining: just days later I learned that she had won, not just a medal, but the respect of her fellow Olympians from around the world, when they elected her to an eight-year term to the highly regarded position as a member of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) Athlete's Commission, which consults with the IOC and serves as a liaison with active athletes.

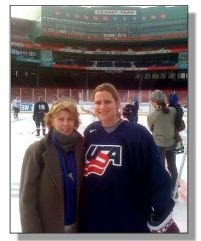

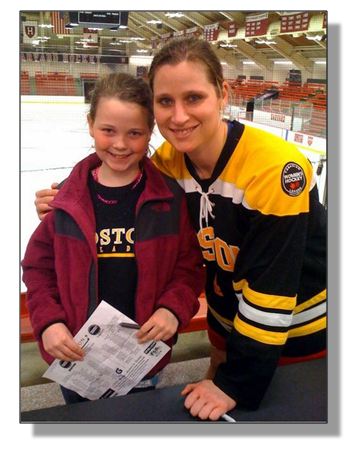

Over the years I have watched Angela play innumerable times, from games in Cambridge for Harvard, to games for the National Team against college all-stars at Northeastern, to road trips to Durham, New Hampshire for a game at UNH in preparation for the Olympics, even a trip to Lake Placid to watch her prepare for the Olympics in Salt Lake City. But, perhaps the one game, other than the ones at the Olympics, I will always remember was her last professional game with the Boston Blades, a team in the Canadian Women's Hockey league in March 2011, against the Toronto Furies, which, fittingly, was played at Harvard's Bright Arena. I didn't know it at the time, but it would prove to be Angela's final game. MomsTeam had run a contest to give away 50 tickets. I decided to take Heloise, my ten-year-old neighbor. It would be Heloise's first time as a spectator watching a team sport. She was mesmerized and became an immediate fan. Angela made it all the more special for Heloise by meeting her after the game and posing for a photo with the awe-struck young girl.

I know that deciding to hang up her skates was a tough decision over which Angela agonized for months, but I also know it was the right decision for her. "To be an elite level Olympic athlete requires complete dedication" Angela said at yesterday's press conference-"and I want to be the best voice I can be for the Olympics."

When she was asked at the press conference about when she made the decision to retire, she admitted that "it was a process which began just after my fourth Olympics in Vancouver in 2010." When Angela finally decided the time was right, she made sure that her USA Women's Hockey teammates and coach, Katie Stone, were the first to know; a sign of respect, of class, and of putting the team ahead of one's self that have been essential parts of Angela's character from the start.

I don't know where Angela's post-athletic career will take her, but I do know that she will be a success in whatever she does. She will, I am sure, continue to make the world a much better place, not only for the athletes she represents on the IOC, but for anyone who gets to know her, as I have, as a person.

As I told her recently; "You have the world in the palm of your hand and so many fabulous opportunities coming your way I am so excited for you."

Thanks

Congratulations, Angela, on your decision and best wishes for the future. To your parents, Karen and Bill, I say, great parenting job! Kudos, too, to your sister, Pam: you have been your Angela's biggest fan (next to your mom!); a sister couldn't ask for more. As for your brother, Billy, I am sure a bit of friendly sibling rivalry helped you to become the remarkable ice hockey player you became; to have been able to share the ice on the same professional team has to make you the best brother Angela could ever have wanted. I know the entire Ruggiero family are proud of what Angela has achieved already in her 31 years, and is excited for her future.

Thanks for the memories, Angela. They'll last a lifetime.