A history of concussion is associated with more than a 3-fold increased risk of a current diagnosis of depression, even after controlling for age, sex, parental mental health, and socioeconomic status, finds a new study. [1]

The study by researchers at Seattle Children's Hospital and the University of Washington adds to the growing body of evidence linking concussion and depression, including the finding of a 2011 study [23] which revealed that adolescents with a history of two or more concussions report more emotional symptoms, as well as physical, sleep, and cognitive symptoms than those without such history.

Researchers found a much stronger association between brain injury and depression than in previous studies, but the dearth of information about the timing of the depression diagnosis in the data made it difficult to draw conclusions regarding causality, says lead author Sara Chrisman, an Acting Assistant Professor at the University of Washington and Seattle Children's Hospital.

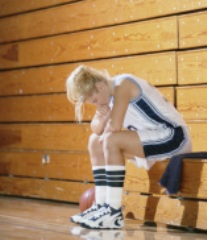

Dr. Christman recommended that adolescents with a history of concussion be more closely monitored for depression, especially since it is associated with significant mental and social problems in teens, including school failure, [8] obesity, [9] substance abuse, [10] and death by suicide. [11]

"Clinicians caring for youth with concussion should be aware of this association and should screen youth for depressive symptoms," Chrisman says.

In an interview with Health Behavioral News Service,[25] Chrisman cautioned that it's not known what exactly might account for higher rates of depression in teens with a history of concussion. It could be the brain injury itself, diagnostic bias due to repeated medical visits for concussion, doctors mistaking symptoms of a concussion for depression, or from the social isolation that they may experience while recovering.

Jeffrey Max, M.D., a psychiatrist who specializes in psychiatric outcomes of traumatic brain injury in children and adolescents at the University of California, San Diego, told HBNS, "In our research, we've found that about 10 percent of the kids had a full depressive disorder or subclinical depressive disorder 6 months after a concussion." Children who have a history of concussion are more likely to develop attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and have difficulties controlling their moods, especially anger, rather than experience depression, Max added.

Unlike Chrisman, however, Max observed that the actual brain injury associated with concussions is probably a major cause of depression in the first few months after injury. "In the clinic, we've certainly seen cases where within hours [of sustaining a concussion], a kid who's never had depression before is suddenly depressed and suicidal. One of our studies found that the brain images in children with traumatic brain injury and depression were actually quite similar to those seen in adults who develop depression as a result of traumatic brain injury."

Too much rest after concussion detrimental?

Dr. Chrisman expressed concern in the study that, while current concussion consensus guidelines [2] recommend that, in the early stages of concussion, youth should not engage in physical or cognitive activities that result in an increase in symptoms, too "many clinicians have interpreted this statement to mean that return to activity should not begin until symptoms have completely resolved."

Such relative social isolation [3] and increase in sedentary behavior," [4] Chrisman noted, can lead to depressive symptoms, pointing to a recent study[5] which found little data supporting rest as a treatment for prolonged concussive symptoms (e.g. for those suffering with post-concussion syndrome) and specifically stating that if "normal activities are restricted for extended periods of time, they [youth] are at risk for secondary problems such as physical deconditioning, anxiety and stress, mild depression, and irritability."

Dr. Christman added that "the approach of waiting until symptoms resolve to begin return to physical activity is more conservative than the treatment used for patients with more severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), where patients are entered into physical rehabilitation programs because of brain-injured symptoms, not despite them." (emphasis supplied).

Indeed, she pointed to new data that suggests patients with severe TBI who

receive earlier intervention fare even better than those for whom

rehabilitation is delayed.[6] A recent review of the medical literature,[7] she said framed this well:

"In medicine, rest is often prescribed by default when the presenting

condition is poorly understood."

"As we learn more about concussive injury, we are finding that although some rest is good, too much rest may be detrimental.," writes Chrisman, pointing to studies that suggest that physical activity interventions for concussion, where youth are slowly returned to activity even while symptomatic, may be more effective than rest.[5,7]

Dissenting view

Rosemarie Scolaro Moser, PhD, Director of the Sports Concussion Center of New Jersey and the author of a recent study[24] on the benefits of cognitive rest after concussion, however, continues to believe that, "overall, cognitive and physical rest, especially immediately following a concussion, is the best course of action," although she advises that "the use of comprehensive cognitive and physical rest, both in the immediate and delayed post concussion period should be well-monitored and applied by an experienced concussion health care professional."

"In cases where there is little improvement, or post concussion syndrome ensues," Dr. Moser says, "rest and activity need to be tailored. For example, if the athlete continues to suffer from significant headaches that are continuous, returning to regular physical exercise (even if noncontact) and full-day academics will likely be unproductive and make the athlete feel worse. On the other hand, if a comprehensive rest period of one (or in some cases) two weeks, has been completed and the athlete, although still symptomatic, feels much improved, then it is appropriate to wean slowly back to school, as can be tolerated, and to work with an athletic trainer to devise a mild re-conditioning regimen."

Dr. Moser says that, at that point, "social activities can be also carefully introduced, especially for morale, as long as the goal remains for the youth to maximize rest, avoid risky exposure, and curtail significant exertion while healing. The concussion doctor needs to work closely with the youth, the family, and the school to help make the important decisions about how to transition back to activity, without rushing the student prematurely, which unfortunately happens too often."

She notes that in her experience most student-athletes seen her in her clinic are "rushed back to school too quickly only to increase their symptoms and recovery time. Often, these students have not been honest about their symptoms initially and return too soon, or their doctors have not monitored their symptoms following the concussion.

Apples and oranges?

Dr. Moser also took issue with the logic used by Dr. Chrisman and her colleague in the current study in reasoning that the standard of early "non-rest" treatment for more moderate or severe traumatic brain injury argued against active use of rest in concussion. "Moderate or severe TBI is a very different phenomenon (greater injury, longer recovery, significant functions more severely affected, different neurochemical processes)," she said, "so the benefits of starting brain work early after the injury outweighs the benefits of rest in order not to lose significant functions."

By contrast, she said, "the loss of such functions (like speech, swallowing, walking, etc) is not characteristic of concussion. I believe that for concussion, or mTBI, the benefits of immediate rest outweigh the benefits of cognitive and physical exertion, especially in the early recovery period. And for those students who have persistent symptoms, but never had the opportunity to engage in that comprehensive week of rest, I say that it is never too late," as her 2012 study[24] on the benefits of strict cognitive rest suggest.

Potential explanations for link

Chrisman identified a number of potential explanations for the observed association between concussion and depression:

- It is possible this association is due to diagnostic bias, or in other words concussion may lead to increased physician visits because so few adolescents visit physicians and this could cause increased diagnosis of depression.

- It is also possible that both depression and concussion occur secondary to other factors for which the study was unable to control.

- The association may actually represents diagnostic confusion, because many of the symptoms of concussion (sleep difficulties, irritability, and fatigue) are also symptoms of depression.

- Some have even suggested that symptoms of concussion (such as sleep disruption) may lead to depression, and a recent study found an association between sleep difficulties and depressive symptoms even a year after brain injury. [12], [13]

Concussion and depression: growing evidence

It was previously thought that youth recovered quickly from concussion, but new evidence suggests symptoms may persist for months or years, particularly after multiple concussions.[14] One of the most concerning symptoms is postconcussive depression.

Data on postconcussive depression comes primarily from the adult literature. Increased diagnoses of depression were found in ex-NFL players with previous concussions, putting them at 1.5 times greater risk. [15] An subsequent study of ex-NFL players found those with two or more concussions had 1.5 times the risk for lifetime depression, while those with three or more had 3 times greater risk. [16] A study in a health maintenance organization in Seattle reported 2 times the risk for depression 2 years after a mild TBI. [17]

As Dr. Chrisman notes, studies on depression from youth with mild TBI are more limited:

- One study of a clinical population found an 11% incidence of new depression in youth 6 months following mild TBI, but these were only in subjects with abnormal brain imaging. [18]

- Studies of depression following mild TBI are complicated by the fact that risk factors for mild TBI (such as low socioeconomic status or family history of mental health issues) are also associated with depression. To more clearly understand the risk for depression following mild TBI requires a comparative population and adequate measurement of potential confounding factors.

- One study of youth in a health maintenance organization in Seattle found twice the risk for depression following mild TBI after controlling for potential confounding, but only for youth without previous psychiatric issues. [19]

- Another study in the same organization found a 1.7-fold greater risk of depression for youth following any TBI. [20]

- The one prospective study of depression and TBI in youth [21] found similar amounts of depressive symptoms when comparing youth with mTBI (no intracranial hemorrhage) to a group of controls 2 years after injury, but 5% of the mTBI patients were diagnosed with major depressive disorder compared with 0% of the controls.