At Detroit's Comerica Park on the night of June 2, 2010, the nationally televised Detroit Tigers-Cleveland Indians game offered children - indeed, Americans of all ages - enduring lessons in compassion and personal responsibility. The teachers were a pitcher and an umpire improbably thrust into the limelight after years in relative obscurity, and their dignity and grace created a "teaching opportunity" for parents, teachers and coaches who seek to shape children's values through sports.

"He didn't say a word, not one word."

With two outs in the top of the ninth inning and his team ahead 3-0, Tigers pitcher Armando Galarraga had retired all 26 Indians he had faced. His lifetime major league record was only 19-17, and he began the season in the minors before the Tigers called him up in mid-May. Now he stood only one out away from a perfect game, a feat accomplished by only 20 other pitchers in major league history.

Immortality seemed assured when the next hitter, Cleveland rookie Jason Donald, tapped a soft grounder fielded cleanly by Tigers first baseman Miguel Cabrera, who tossed to Galarraga covering the first base bag. With the ball in his glove, Galarraga's right foot hit the bag a full step or more ahead of the runner. The play was not even close. But first base umpire Jim Joyce called Donald safe. The mistake was unusual for Joyce, a ten-year veteran whom the players themselves considered to be the major leagues' best umpire.

Long after memories of most of the 20 previous perfect games fade, fans will remember what happened in the next few hours. Rather than argue or throw a tantrum on the field, the 28-year-old Galarraga maintained his composure, smiled, completed his one-hit shutout by retiring the next hitter, and walked into the Tigers dugout without confronting Joyce.

"I don't know if I would have handled it the way Armando did," said Tigers catcher Gerald Laird, "It really says a lot about him." "If I had been Galarraga," umpire Joyce agreed later, "I would have been the first one standing there [yelling]. . . . He didn't say a word, not one word."

"I just cost that kid a perfect game."

In the umpires' dressing room a few minutes after the game, Joyce asked to see a video replay of the critical call, which showed clearly that his stunning mistake had cost Galarraga a place in the record books. The umpires' room is normally closed to the press, but Joyce asked to speak with reporters. Umpiring crew chief Derryl Cousins offered to answer questions for his colleague, but Joyce insisted on fielding all questions personally.

He proceeded to do something rare for umpires and referees: he admitted his error, unequivocally and without alibi or excuse. "I take pride in this job," Joyce said, "and I just cost that kid a perfect game. I had a great angle, and I missed the call."

"Sometimes life just isn't fair for people"

The tearful Joyce then asked to meet with Galarraga before the two left the ballpark, and he apologized to the pitcher face-to-face. "I think it's only fair," said the veteran umpire in his dressing room, "The whole world saw it. I had to do the right thing."

Despite his lost opportunity, Galarraga immediately empathized with the distraught umpire, shook hands with him, and forgave him. "I give him a lot of credit," said the pitcher, "He really felt bad. . . . His body language said more than a lot of words. His eyes were watery. He didn't have to say much."

"Nobody's perfect, everybody's human," Galarraga explained, "I feel terrible too because he's a good umpire, and sometimes life just isn't fair for people."

"I knew I had to do it"

Major League Baseball offered to spare Joyce the Detroit fans' expected wrath by replacing him for the next afternoon's game, but he rejected the offer. After a sleepless night, the umpire would not hide from what had happened. "If I wouldn't have shown up here, I don't think I could have faced myself . . . I knew I had to do it and wouldn't walk away."

The drama continued the next afternoon when Tigers manager Jim Leyland sent Galarraga to home plate before the game to give the team's lineup card to Joyce, who was calling balls and strikes that day. Pitcher and umpire shook hands and embraced again.

After Joyce surreptitiously wiped away a tear, Galarraga patted him on the shoulder and said that he had "already turned the page."

"The sportsmanship that he holds in his inner being," responded the grateful Joyce, "is right there with the best of them."

"This is just spilled milk"

"I was waiting for" fan hostility, said Joyce, and "I was ready to accept it." He did not have to wait long because a website, "firejimjoyce.com," appeared within hours. Death threats and vulgar insults laced the umpire's Facebook page and those of his children, hostile phone calls came to his wife at home in Oregon, and attacks defaced his Wikipedia biography.

Hostility, however, quickly turned to abiding respect from coast to coast. At home plate the next afternoon, the beleaguered umpire received a standing ovation from fans who respected his candor; and who knew that if Galarraga could forgive an honest mistake, then they could too. At Detroit's Metro airport after the Indians series ended later that week, Joyce was astounded when people shook his hand and thanked him for promptly owning up to his mistake. "I had a police officer say ‘Thank you.' I said, ‘No, thank you.' This guy puts his life on the line every day. I call balls and strikes. These are the people you should thank."

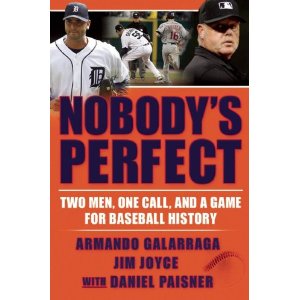

The bond between pitcher and umpire continued in July, when they jointly presented the ESPY Awards before a national television audience. The two have since co-authored a book, Nobody's Perfect: Two Men, One Call, and a Game for Baseball History, which Atlantic Monthly Press published on the first anniversary of the game that brought them together. (It is a book I think both parents and children alike would enjoy for humanizing both men and telling a compelling story.)

Joyce reports that letters and emails have been 99% positive, including those from school children. One message came from 11-year-old Nick Hamel, a baseball fan who has spinabifida. Nick wrote that his therapist had told him "not to cry over spilled milk. . . . Tell Mr. Joyce that this is just spilled milk."

This story's lessons: Parents, teachers and coaches are children's best role models

"Americans have a profound longing for heroes - now perhaps more than ever," wrote journalist Hampton Sides last month in Newsweek. Perhaps the gallantry of Armando Galarraga and Jim Joyce resonated so quickly because the two men provided a refreshing antidote to the crimes, steroid abuse, trash talking, and similar eyesores that besmirch so much of professional sports these days.

Perhaps, too, their story resonated because attention turned quickly to America's children. "Those of us whose kids play sports, or who idolize athletes," said a Baltimore Sun editorial, "have pitiably few opportunities to point to a contemporary sports figure and say to our child: ‘There, that's a good example for you. That is the right way to behave.'"

As the Sun suggested, whether the sterling example of sportsmanship displayed by Armando Galarraga and Jim Joyce actually influences children does not depend on the two men alone. The answer depends more on whether parents, teachers and coaches talk with the youngsters about their story and encourage them to draw lessons from it. Face-to-face communication is key because it adults in the community, not the pros we watch only on television or from the stands, who will always be our children's most influential role models.

If we need any testament to the power of face-to-face communication, we need to look no further than Galarraga himself, who credited his mother and father for his restrained reaction when he lost the perfect game. "This is how my parents taught me," says the pitcher. "All the time, when I was growing up, they taught me that in hard moments I should always have a smile. It does not matter how you feel inside. It matters how you show on the outside."

Plusses and minuses

Have adults communicated with children about the example set so dramatically by Galarraga's compassion and Joyce's swift acceptance of personal responsibility? The fateful call remains available on YouTube, but the record, sadly, is mixed.

On the plus side, the Grand Rapids Press reported that a local U-11 traveling baseball team quickly followed their coach's lead and voted unanimously to name themselves "Team Galarraga." Said one team member, "Armando is a role model because he reacted to the blown call with class."

Nine days after Galarraga's feat, however, class took a backseat when a similar call decided a Virginia high school Group A semi-final baseball game. With two outs in the bottom of the 11th inning, the Virginia High batter hit a grounder to the Chatham High shortstop, whose throw (according to the account in the Bristol Herald Courier) appeared to beat the runner by a step. The umpire called the runner safe as the winning run crossed the plate.

According to the Herald Courier, Chatham's coach watched his players "turn the visiting-side dugout into to a hornets' nest of flying gloves, thrown batting helmets and pushed-over ball buckets as they exited the diamond." The coach reportedly "didn't know what to tell his team."

Perhaps the coach could have started with two words: "Armando Galarraga."

Sources: The Galarraga-Joyce story was reported in dozens of news stories, including Ted Kulfan, A Day Later, Galarraga Still Calm, Detroit News, June 4, 2010, p. B4; Sheldon Ocker, Stepping Up to the Job, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 6, 2010, p. C-1; Mark Snyder, Call of a Lifetime, Detroit Free Press, June 5, 2010, p. B1; Tom Verducci, A Different Kind of Perfect, http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1170587/1/ind... Perfect Sportsmanship, Baltimore Sun, June 5, 2010, p. 11A (editorial). Also Armando Galarraga and Jim Joyce, Nobody's Perfect (Atlantic Monthly Press 2011), p. 202; Dean Holzwarth, Club Makes Right Call With Team Galarraga, Grand Rapids (Mich.) Press, July 25, 2010, p. C1; Jim Sacco, Rally, Controversial Call Push Virginia High Into State Finals, Bristol (Va.) Herald Courier, June 12, 2010.